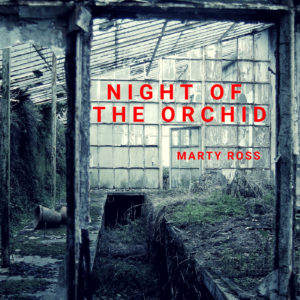

Download our spooky Halloween release today: NIGHT OF THE ORCHID

If you’re a fan of Marty’s brilliant work, why not have a gander at his blog entry below about this project…

BEGINNINGS – by Marty Ross

Playwriting turned out to be s-o-o-o easy. After starting out with the usual naïve andforedoomed attempts to write screenplays (although one of these evolved, years later, intomy popular BBC radio serial Catch My Breath), I wrote my very first stage play Night of theOrchid and began sending it around. Within a couple of months, an actor / producer called Elaine Hallam was on the phone telling me I was set to be the British David Lynch and that she wanted to set up a production and herself play the lead role of Madeleine Loughran.

In no time at all she had organized a rehearsed reading before a live audience at the Liverpool Everyman, where she had connections: and this wasn’t to be a bog standard “sitting in bucket chairs / heads in the script” reading – no, director John Doyle (later a big hit on Broadway with his revival of Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd) had in mind a full week of rehearsals, leading to a pretty much fully staged performance on the set of their current production of John Webster’s The White Devil – they had drawn a link between the verbal and dramatic style of Orchid and the more Gothic side of Jacobean tragedy.

Rehearsals and performance went well. The actor playing Aunt Mary said I wrote like TS Eliot (!), an actor came to the performance who knew Doug Bradley of Hellraiser fame and said this would make for the next big British horror movie (!!), a female student in the audience said she couldn’t believe a man had written it and that I had written a feminist statement (!!!). Elaine Hallam told me herself, over coffee, that “you’re going to be so famous”. I headed home to Glasgow, convinced mine and Orchid’s path to greatness lay straight ahead.

Except… nope. It didn’t work out that way. Not at all. Not remotely. Not even close. Overthe months that followed, Elaine touted the play damn near everywhere, the NationalTheatre even – at one point, I was told, a Very Famous British Actor had it on his bedside table in Hollywood with an eye to playing Paul. (Except he got cast as a Royal in a US TV movie and that took precedence). It turned out an actual production was going to be much harder than initial hints had suggested: I was not to be an overnight success after all. Far from it.

Had I been less young and naive, I might have seen the disappointment coming: the bias in British “new writing” theatre is perennially towards the realistic state of the nation play ,set in the caff around the corner, ticking the obvious boxes on the big obvious social issues of the day: here was a flamboyant Gothic fantasy about a woman having a passionate sexual relationship with a ghost inside a supernaturally rejuvenated glass house attached to a remote Scottish country house. (The reader at the Stephen Joseph Theatre in Scarborough proclaimed it “a little too redolent of the Hammer House of Horror” – high praise to me, who revered the best of Hammer as valid and poetic and beautiful, but he of course used the term pejoratively). Furthermore, it wasn’t a play that could easily fit into the small black box venues that dominate the new writing scene: at the very least this required an on stage evocation, however abstract, of a vast ruined Victorian glass house -one that halfway through starts sprouting psychedelically weird vegetation. Typical playwright: I hadn’t even thought about how this might be done, I just figured I’d leave the practicalities to a future director. No such director presented him/herself.

And I moved on: almost immediately upon returning from Liverpool to Glasgow, I wrote another play, still very Gothic but set in a grittily realistic tenement Glasgow – and soon that got shortlisted for a prize and got a couple of rehearsed readings at prestigious London theatres and seemed the more “practical” play to pressing on with.

Except that didn’t get produced either and I soon realized that I was doomed to be a tortoise in a generation of theatrical hares… a tortoise with a wooden leg and a concrete block tied to its neck.

And when my “break” did belatedly come, it came not in theatre, but in radio / audiodrama, a medium – it turned out – more suited to my kind of dramatic sensibility, with its greater imaginative freedoms and fluidity and, at least relatively speaking, lesser inclination to outright bias against “low” genres like horror. And indeed Elaine Hallam had suggested, back when she was touting Orchid, that it might work as a radio play. But at a time when the only market for radio drama was the BBC, Orchid was too much of a full tilt horror story for Radio 3, too sexual and violent for Radio 4, so that idea seemed a nonstarter.

So Orchid was shelved and meanwhile I went on and wrote, and had produced, a ton of other things, for the BBC, for Big Finish, for Wireless and for Audible – 27 separate productions in the last 16 years – , finding the home in audio drama I’d never found in the theatre. And again the idea of an audio drama of Orchid resurfaced. Back in 2010, Wireless formed an alliance with a venture called 3D Horror Fi, producing several dramas in binaural format, including my own Blood And Stone. I immediately wrote an audio version of Orchid as a follow up, but the Horror Fi venture came to a premature end, and once again Orchid was shelved.

Until a couple of years ago, when Mariele Runacre Temple at Wireless was looking for a potential Christmas release – I suggested that revised script of Orchid: ghost stories are a Christmas tradition and this ghost story was even set in a snowbound landscape. Mariele was enthusiastic about production, but thought it might be more of a Halloween play than a Christmas one, so after a bit of further delay it finally found a director in Paul Blinkhorn unintimidated by the play’s blend of horror, “visual” flamboyance, transgressive eroticism and heightened language, a director moreover insistent on the play’s “Scottishness” (previously I hardly cared for what accent it got done in, so long as it got done: the Liverpool performance had an all English cast) – I myself maybe needed him to remind me how Scottish my inspiration was – and, indeed, a character like Miss Kyte might not make any real sense outwith the context of Scottish Presbyterianism.

And so now at last it’s produced and can go before an audience – it has taken one hell of a long time, but maybe that’s not so inappropriate for a play about things left for dead taking on a whole new vivid life many years later.

INSPIRATIONS

1.) FOREST

All I really got out of formal education was traumas and nightmares to last me a lifetime.One of the milder traumas came when, as a very young kid, I was taken, like millions of Glasgow school kids before and since, to a place in Bellahouston Park called the Fossil Grove. Essentially one goes into a glass roofed structure and in there one sees… well, the ghosts of trees, or tree stumps, at least. I didn’t grasp the science as a kid, and hardly do now, but effectively these are trees that have been turned to stone – grey and dead and ghostly. The smell of damp stone is still with me today. When I Google it now, it doesn’t look that spectacular, and I’ve been loathe to go back for fear of disappointment, but to meas a kid there was something deeply disturbing about this indoor “landscape”: they say the things that frighten us are the things that confuse distinctions – between living and dead (ghosts / vampires / zombies), human and animal (werewolves), solid and liquid (slimyblobs from planet X)… well, here was a ‘forest’ that was indoors, a forest that embodied death rather than life. For some while afterwards, I would have nightmares of being trapped all alone in that building. In those nightmares, lay the “root” of Orchid’s deathly glass house.

2.) ARCHITECTURE

A somewhat less troubling school trip was to Glasgow’s People’s Palace – a museum, in effect, of working class social history in the city. That’s well and good, but it was the architecture that left its mark, perhaps, on Orchid – a grand, palatial building with a huge glass house attached, almost as big as the main building and filled with lush tropical plants and trees

3.) BODIES

One day, in a long ago Sunday supplement, I came across an article commemorating the umpteenth anniversary of Kenneth Tynan’s 1960s “erotic revue”, O Calcutta. It had a small black and white photograph of two dancers in the show, one male and female, both naked and twined around one another in a tight embrace. It was a powerful image – not really explicit, rather shadowy, with them wrapped too tight around one another for much physical ‘detail’ to be visible, but it occurred to me that a drama built around two characters twined around one another as nakedly as that might make for a more interesting show than one where the characters kept their clothes on. That drama turned out to be Night of the Orchid.

4.) GHOSTS

Another obvious influence is the grand tradition of the old school British Ghost Story, and certainly Night Of The Orchid features many of the classic elements. But, though I love that tradition, Orchid in many ways is a subversion of that tradition as much as an example of it.

It’s a tradition, in its most classic formation certainly, defined by a few distinct features – 1)It is pointedly more “tasteful” and “subtle” than “cruder”, more in-your-face forms of horror tale: the vampire story, the zombie shocker, grand guignol etc. The supernatural will be presented as obliquely / fleetingly / ambiguously as possible. Actual physical violence will be kept to a minimum, if present at all. 2)Though a Freudian might see the sexual behind all horror imagery, the existence of sexuality is often barely acknowledged in these stories: all those tales by M.R. James (the writer who more than any other defines the “classic”ghost story) may be filled with celibate male academics being assailed by hairy ghosts with pink mouths, sucking mouths that appear under their pillows, female ghosts with jagged bloody holes in the middle of their bodies, hairy blood-sucking spiders scuttling out of a tree where a female witch is buried, phantoms that materialize out of the celibate’s bedsheets etc etc – but though Freudian interpreters might have a field day with this, there is rarely any acknowledgement in the tale itself that human sexuality exists in the first place.

With that in mind, Night Of The Orchid creates a scenario in which sexuality asserts itself with the most carnal, Dionysian explicitness (we’re back to those naked lovers entwining),in which violence explodes on the scene in the reddest hues, in which the fantastic manifests itself in the brightest, boldest colours and the clearest possible focus. As such (from someone, I repeat, who loves the traditions of the subtle old school ghost story), Night Of The Orchid is a kind of “experiment in explicitness” – what, I was asking myself, if all the things which the traditional tasteful ghost story keeps shut out of sight (violence, sex etc) were allowed to erupt down stage centre in a great big bright spotlight?It’s a (very) young man’s play, bear in mind, with a punkish energy to it: for Sid Vicious puking in a plant pot at EMI, substitute me being similarly “badly behaved” within the tasteful precincts of the genteel English ghost story.

5.) VIOLENCE

But it wasn’t any old explicitness I was after. When the Liverpool Everyman paired that first performance with their production of Webster’s “The White Devil”, they had, I like to think, the right sort of intuition: the violence I sought to evoke was less that of the bog standard splatter movie than that of the more grandly gruesome sort of Elizabethan or Jacobean tragedy – Titus Andronicus, The Revenger’s Tragedy, The Duchess of Malfi: operatic bloodshed blended with a matching flamboyance of language.

6.) SURREALITY

Another big influence was Surrealism – and I don’t just mean the sort of tame surrealism they sell on calendars and T shirts. There’s a kind of extremist surrealist eroticism which was a big influence on Orchid: wild, transgressive stuff such as the sculpture and drawing of Hans Bellmer, the paintings of Leonor Fini (I recall it was Whitney Chadwick’s “Women Artists & The Surrealist Movement”, featuring a lot of Fini’s work, which I was reading on the train down to that first Liverpool reading) & the writings of Georges Bataille, such as Literature & Evil, Erotism and his novellas The Story Of The Eye and Madame Edwarda: serious boundary pushing stuff. Predecessors of Surrealism like Baudelaire (“Les Fleurs de Mal”, natch!) and Lautreamont (“Maldoror”) were in the mix: work which isn’t afraid of staging an all out assault on all notions of good taste and artistic decorum. (Bear in mind that Surrealism’s founder, Andre Breton, dismissed pretty much the whole canon of “classic” literature – except for the British Gothic novel, which he collected obsessively, particularly revering Mathew Lewis’ “The Monk”, which has many stylistic similarities to Orchid.)

Some of this emphasis may, of course, be overlooked in this audio version: the stage version would have featured copious nudity, both male and female (if I could have got an erect penis on a public stage, I would have done it!) – by definition, with an audio drama,the individual listener will see as much or as little physical explicitness as s/he has a mind to. I’d certainly encourage listeners not to be afraid of “seeing” things fairly explicitly. That applies to the landscape of our glass house, likewise. When I was visualising the reborn vegetation, I was again thinking in terms of a kind of hallucinatory explicitness – I thought of the landscapes of Salvador Dali or the forests and jungles of Max Ernst: sublime, strange landscapes seen not veiled in vague mists but with a kind of LSD clarity and colour and focus, more Ken Russell or Apocalypse Now than misty black and white: a lysergic aesthetic. But you’re the listener: after all this time buried in the shadows of obscurity, it’s time at last for a fully produced, fully realized Night Of The Orchid to go before the public and for you to “see” it in terms of brighter, bigger visuals than could probably ever have been achieved on the stage. It’s a big deal to me – my lost child rescued and restored after years of exile.

I’d like to thank those who helped and inspired all through this long process: most obviously Elaine Hallam, Mariele Runacre Temple, Paul Blinkhorn and the marvellous cast he assembled to make the surreality real at last.

MARTY ROSS

October 2018